When you read your Bible, do you read it in English?

If you do, you owe a debt to William Tyndale.

He was not the first person to attempt to translate the Bible into English, or the person who finally completed the task, but to say that William Tyndale was the one person who did more to get the Bible translated into English than any other is not likely an exaggeration.

October 6 marks the anniversary of the death of William Tyndale by strangulation and burning for the crime of heresy. His heresy? Translating the Bible from its original languages (Greek and Hebrew)1 into the vernacular (English) so that it could be read by all and not just those educated in Latin.

William Tyndale was an English Bible scholar, linguist, and Reformer. He is well-known for his translation of the Bible into English during a time when owning any portion of a Bible written in English, or even memorizing sections in English was forbidden in England. (His translation work was done almost exclusively while living as a fugitive in Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium).

Ironically, vernacular translations of Scripture were already rather common, particularly in the East, plus most of Western Europe, but not in England, where is was vehemently opposed as a threat to religious and civil authority. Thousands of Tyndale Bibles were printed at underground presses on the Continent and smuggled into England.

Lord High Chancellor of England, Sir Thomas More opposed the Protestant Reformation as heresy and saw William Tyndale as a threat. He wrote several books debating Tyndale and refuting his translation as heresy.

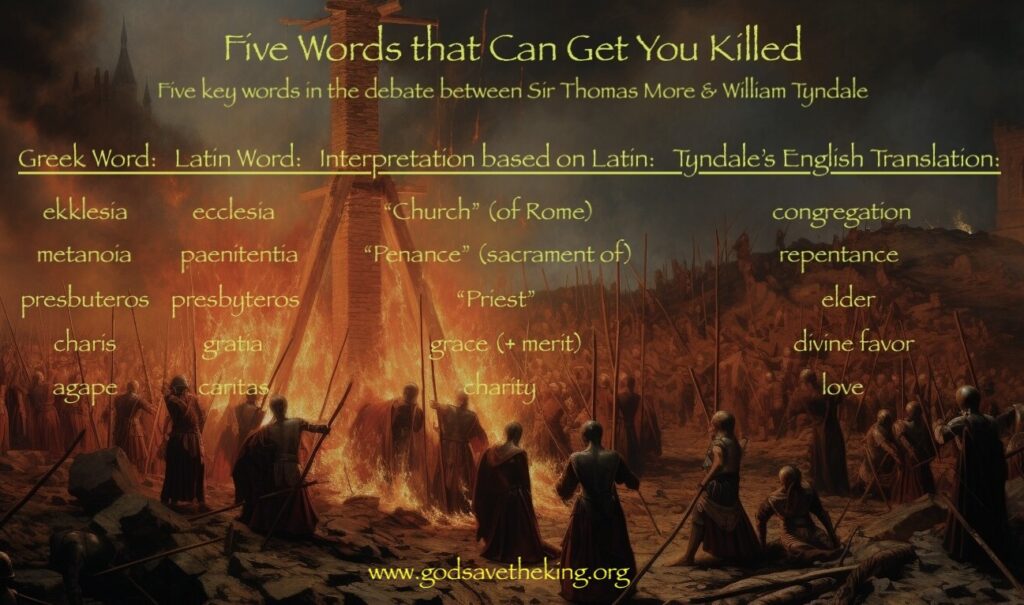

When studying Tyndale’s English translation of the Bible, More focused on five words he felt were a greater threat than any others because their “biased” translation undermined both religious and civil authority. Ironically, it was More who accused Tyndale of “avoiding common translations” and using “biased” words in their place.

| Greek Word | Latin Word | Interpretation based on Latin | Tyndale’s Translation |

| ekklesia | ecclesia | “Church” (of Rome) | congregation (local) |

| metanoia | paenitentia | “Penance” (sacrament of) | repentance |

| presbuteros | presbyteros | “Priest” (clergy) | elder (not necessarily clergy) |

| charis | gratia | grace (plus “merit”) | divine favor |

| agape | caritas | charity | love |

The Greek word ekklesia, although maybe best translated “assembly” is far better translated “congregation” than “church”–especially when the interpretation is claimed to mean the “Church of Rome” as opposed to a local assembly (which is its most common biblical use). That the word ekklesia should be interpreted to mean “The Church” (of Rome) in biblical use is a classic example of eisegesis,2 and fundamentally illogical.

Likewise for the Greek word metanoia. Meta means “to change” while noia means “the activity of the mind”.3 Although “repentance” is not best, it is far better than “penance”–especially when this will be interpreted as the sacrament of penance exclusive to the Roman Catholic Church–a meaning utterly foreign to the etymology of the Greek word. Metanoia is best translated “to change one’s thinking”.

The English word “presbyter” is a transliteration of the Greek presbuteros, and means “an elder”. Etymologically, it can never mean a “priest”, which would be the Greek hiereus. Once again, to read into the translation a meaning that it not etymologically present is faulty hermeneutics (eisegesis). This one is beyond obvious and a deliberate bait and switch by some denominations to make the Bible mean what they want.

Charis can indeed be translated “grace” but once again this has a peculiar application and definition according to the Roman Catholics, where grace must be mixed with “merit” in order to be efficacious. In this case, Tyndale was simply implying that the term is more general than the exclusive Roman Catholic interpretation/application.

But the word More considered worst of all was translating agape as “love” instead of “charity”–believing that the unlearned would confuse God’s love for something baser.

More was beheaded by order of Henry VIII in July of 1535 for ultimately refusing to sign the Oath of Supremacy,4 his refusal to acknowledge Henry’s annulment from Catherine of Aragon,5 and thereby the Oath of Succession.6

Tyndale lived his life on the Continent as a fugitive, hiding from English agents sent to find him and “bring him to justice”. One of these agents deceived Tyndale into supposed friendship and betrayed him. He was strangled and burned at the stake as a heretic on October 6, 1536.

- Not a translation from Latin, which is not an original language. A translation from Latin into English would be a translation of a translation and could therefore possibly transpose any errors or biases into the target language. Tyndale wanted a translation from the original languages, Greek and Hebrew, in order to specifically avoid this possibility. ↩︎

- Reading a meaning that is foreign to the text into the text. ↩︎

- The activity or action of the mind (verb) as opposed to the mind itself (noun) which would be the Greek nous. ↩︎

- That Henry VIII, King of England was also head of the Church of England. ↩︎

- More was a hardliner, believing that annulment or divorce required the permission of an ecclesiastical leader. And the only ecclesiastical leader who could give “permission” to a king was the Pope. In More’s mind, regardless of why, Henry VIII was required to remain married to Catherine of Aragon no matter what. ↩︎

- That the children of Henry VIII by Anne Boleyn (ultimately their daughter Elizabeth I) were not legitimate heirs of the throne of England. ↩︎