(26) And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying: (27) Also the tenth {day} of this seventh month {shall be} the Day of Atonement. It shall be a holy convocation for you; you shall afflict your souls, and offer an offering made by fire to the Lord.

[Leviticus 23:26–27 NKJV]

Scriptures: Leviticus 16; 23:26–32; Numbers 29:7–11. Hebrews 8–10.

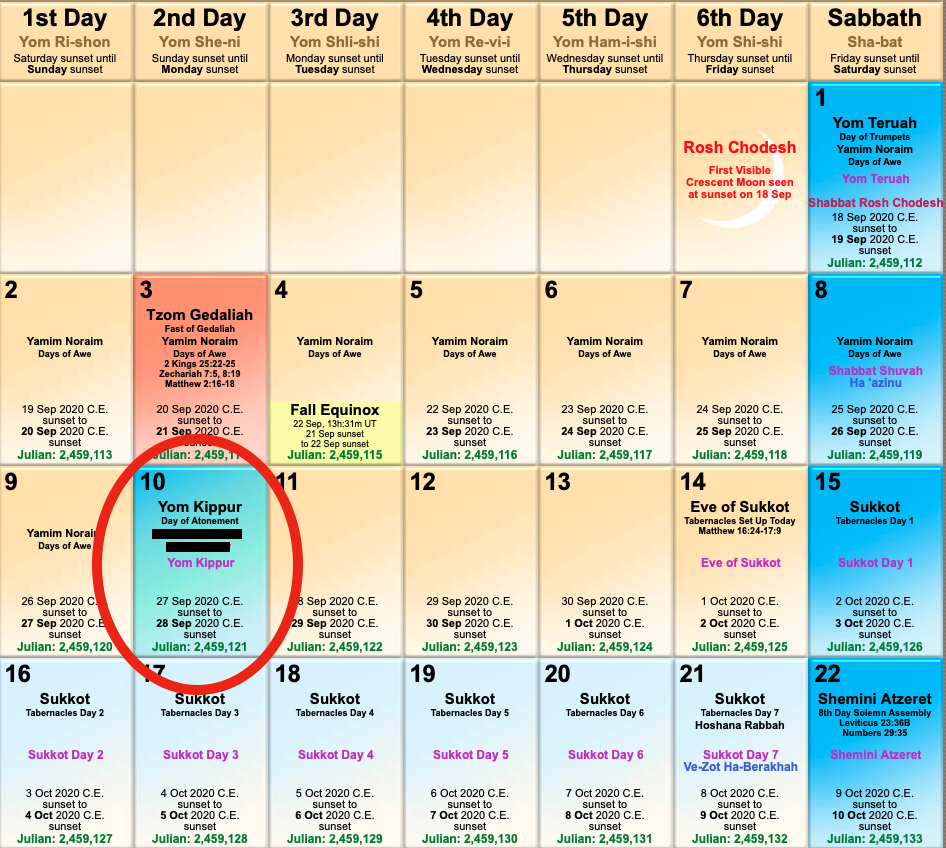

Yom Kippur begins at sundown Sunday September 27, 2020.

Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement, is the sixth feast of the Hebrew religious year. It is the most solemn of all the feast days, and the most holy day on the Jewish calendar. It is the national day of spiritual cleansing for the Jewish people.

Historically, this was the one day each year the High Priest was allowed to enter the Holy of Holies. This solemn feast procured the cleansing of all sin, transgression, and iniquity from the entire nation for another year.

God’s world is great and holy. Among the holy lands in the world is the holy land of Israel. In the land of Israel, the holiest city is Jerusalem. In Jerusalem, the holiest place is the Temple, and in the Temple, the holiest spot is the Holy of Holies.

There are seventy peoples in the world. Among these holy peoples is the people of Israel. The holiest of the people of Israel is the tribe of Levi. In the tribe of Levi, the holiest are the priests. Among the priests, the holiest is the High Priest.

There are 354 days in the year. Among these the holidays are holy. Higher than these is the holiness of the Sabbath. Among the Sabbaths the holiest is the Day of Atonement—the Sabbath of Sabbaths.

There are seventy languages in the world. Among the holy languages is the holy language of Hebrew. Holier than all else is the language is the holy Torah, and in the Torah the holiest part is the Ten Commandments. In the Ten Commandments, the holiest words of all words, is the name of God.And once during the year, at a certain hour, these four supreme sanctities of the world were joined with one another. That was on the Day of Atonement, when the High Priest would enter the Holy of Holies and there utter the name of God.

[Adapted from The Dybbuk by Saul Ansky]

The Day of Atonement was marked by two special sacrifices—two goats—one for the Lord, and the other “for Azazel,” or “for the scapegoat”. One goat was slain, and its blood sprinkled on the Mercy Seat of the Ark of the Covenant within the Holy of Holies by the High Priest. The other is particularly unique. The second goat (“for Azazel/the scapegoat”) had the sins of the people placed upon it by the High Priest, and then it was led into the wilderness to die.

A thorough examination of the scapegoat ritual is beyond the scope of this article, suffice to say that as the Old Testament scapegoat bore the sins of the Hebrew nation, so did Jesus Christ bear ours sins that we could be set free. For the Jewish people, there still awaits an historical fulfillment of this feast. Followers of Jesus find spiritual fulfillment presently.

Although John the Baptist referred to Jesus as the lamb of God, and this clearly points to the Feast of Passover, there is likely a double meaning here. When we read the crucifixion narrative it is clear that the Jewish religious leaders made Jesus a scapegoat.

A close examination and comparison of how the world practices scapegoating, how the Jews embraced the scapegoat ritual under the Mosaic Law, and how Jesus Christ fulfilled this type reveals an extraordinary truth.

In secular culture, a scapegoat has come to mean a person who is blamed for the wrong-doings of others—usually for reasons of expediency—meaning that those doing the scapegoating tend to be aware that the person being scapegoated is not legitimately at fault. Additionally, those doing the scapegoating tend to rationalize or even deny their own sin and culpability.

In Jewish culture however, where we get the term scapegoat, the ritual performed by the High Priest on the Day of Atonement “transferred” the guilt of the people to the goat, and then the goat was sent into the wilderness to die.

This distinction could not be more critical. The systems of the world are rife with trouble precisely because people tend to blame others for sins they didn’t commit while simultaneously neglecting their own sin and responsibility. It is a tragic reality that the practice of scapegoating remains rampant throughout the world and goes largely unnoticed, or even worse, rationalized. It is the Judeo-Christian ethic that has brought attention to the fact that we all must face our own brokenness, and find remedy and reconciliation with God and others through repentance and forgiveness. And yet, even the solemnity and introspection of the Day of Atonement is but a pale shadow that finds its fulfillment in Jesus Christ. Well did the prophet Isaiah describe the suffering Messiah when he wrote:

(3) He is despised and rejected by men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief. And we hid, as it were, {our} faces from Him; He was despised, and we did not esteem Him. (4) Surely He has borne our griefsand carried our sorrows; Yet we esteemed Him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. (5) But He {was} wounded for our transgressions, {He was} bruised for our iniquities; The chastisement for our peace {was} upon Him, And by His stripes we are healed. (6) All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned, every one, to his own way; and the Lord has laid on Him the iniquity of us all.

[Isaiah 53:3–6 NKJV]

The apostle Peter later quotes Isaiah and makes a clear allusion to Jesus as our scapegoat, bearing our sins.

Who Himself bore our sins in His own body on the tree, that we, having died to sins, might live for righteousness—by whose stripes you were healed.

[1 Peter 2:24 NKJV]

But the reality of the New Covenant goes even further declaring that Jesus not only bore our sins, but became sin for us so that we might become the righteousness of God in Him.

For He made Him who knew no sin {to be} sin for us, that we might become the righteousness of God in Him.

[2 Corinthians 5:21 NKJV]

The Jewish people believe that on Rosh Hashanah, the Head of the Year (Jewish civil New Year), God writes a person’s “fate” for the coming year in the Book of Life. Then on Yom Kippur, God seals that fate. The ten days in between, known as the Days of Awe, are the person’s opportunity to “change their fate” via repentance.

Yom Teruah, or the Day of Trumpets, is the entryway into the Days of Awe. The blast of the shofar (ram’s horn) is understood to be the wake-up call to repentance. People of faith then spend the next ten days in introspection and repentance before God, as well as making amends for sins committed against people. For followers of Christ, the Mosaic feasts serve as examples, or models if you will, that were designed to point to the person of Jesus Christ, and impart spiritual truths that are a part of His victory on the cross of our behalf. Although we are no longer required to blow shofars, “afflict our souls” or sacrifice goats, we are encouraged to “keep the feast” through the cross.

Jesus of Nazareth is indeed our Scapegoat, Who bore our sins that we might become the righteousness of God in Him. The Days of Awe and Yom Kippur are a great opportunity for followers of Christ to prepare for the coming year by acknowledging all that Jesus accomplished for us and embracing an attitude of repentance, reconciliation, and renewal.